By Dhara Ranasinghe, Nell Mackenzie and Yoruk Bahceli

LONDON (Reuters) – The selling gripping the world’s biggest bond markets, on fears that stubbornly high inflation will keep central banks hiking interest rates for some time, is a warning sign that riskier assets will likely be next in the firing line.

After all, if central banks hike rates for longer than expected, that raises risks of a sharp economic downturn, a scenario markets have put aside given robust economic data.

That means bond pain may soon weigh on equities and credit, markets that have held up well so far.

This week’s stronger-than-expected February inflation data from France, Spain and Germany has led traders to price European Central Bank rates peaking near 4%, following similar moves in U.S. money markets.

That has pushed 10-year bond yields across the euro area to levels last seen during the bloc’s 2011-2012 debt crisis. Yet, European shares are not far off one-year highs.

And while U.S. 10-year Treasury yields rose almost 40 basis points in February – their biggest monthly jump since September – the S&P 500 ended the month down just 2.6% and is up almost 3.5% so far in 2023.

“We are starting to reach a level in pricing on rates that any move up in yields is becoming more problematic,” said BlueBay Asset Management chief investment officer Mark Dowding.

“There will be a landing for the economy and if we see more robust data and inflation staying high it will bring the idea of hard landing back into prospect,” Dowding said, noting that he had closed out of a position betting on further weakness in longer dated bonds and turned more negative on risk assets.

In its weekly note, the BlackRock Investment Institute said it preferred short-term government bonds and investment-grade credit over long-term government debt and was underweight developed market equities because “they’re not pricing the recession we see ahead.”

HOT INFLATION

Expectations that inflation would ease and central banks could pause aggressive tightening soon had already turned around in February on resilient data.

But rate-rise expectations have taken another leg higher this week, led by Europe. Data on Wednesday showed no let-up in stubborn price pressures in Germany. Spain and France posted unexpected inflation rises on Tuesday.

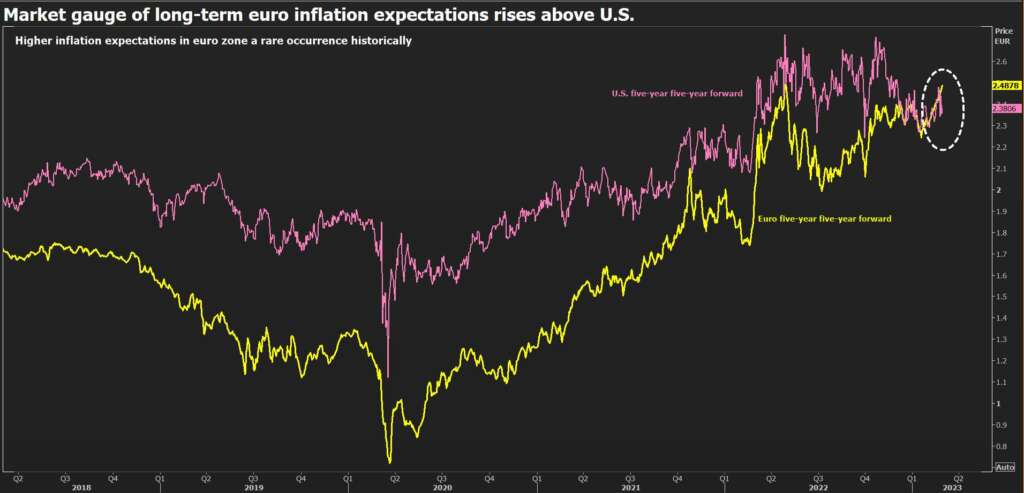

A key gauge of the market’s long-term euro zone inflation expectations has risen to 2.51%, its highest level in over a decade, pushing above U.S. peers in a rare occurrence.

Euro vs US market inflation expectations https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/mkt/lbpggljkepq/euro%20vs%20us%205y5y.png

Deutsche Bank strategist Jim Reid said the rates repricing in Europe was “pretty astonishing” given that just a year ago there were doubts about whether the ECB would be able to lift rates at all and German Bund yields briefly turned negative as war in Ukraine broke out.

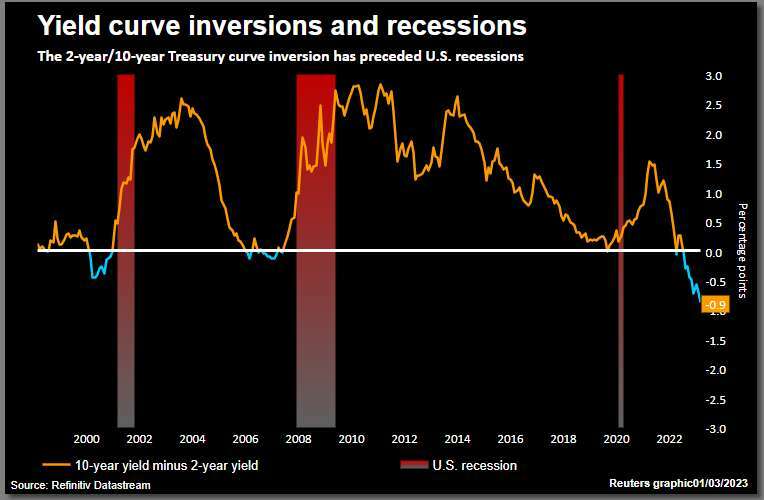

U.S. and German bond yield curves meanwhile remain deeply inverted, with short dated borrowing costs well above longer dated peers in a classic sign of looming recession.

“Major economies still have a long way to go to achieve comfortable inflation levels. As a result, policy rates are still at risk of staying higher for longer, and fixed income markets have adjusted accordingly,” said Bruno Schneller, a managing director at INVICO Asset Management. “Equity markets appear expensive when considering the possibility of prolonged higher rates.”

Patrick Saner, head of macro strategy at Swiss Re, added that rising government bond yields also made risk assets relatively less attractive.

A classic 60/40 portfolio of equities and bonds now yields less than six-month U.S. Treasury bills for the first time in around 20 years, he noted.

The U.S. yield curve is deeply inverted https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/mkt/jnvwyalekvw/USYC.PNG

BUY BONDS?

And while government bonds were seen vulnerable to further selling, higher yields are still viewed as a buying opportunity.

Snigdha Singh, co-head of fixed income, currencies and commodities trading for EMEA at BofA, expected investor allocations to return to bonds, especially in Europe where negative yields have disappeared.

“In sovereign markets now, 10-year German bond yields are north of 2.70%. So I would expect certainly to see those kinds of allocations take place,” Singh said.

UBS strategist Rohan Khanna said he suspected investors still wanted exposure to longer-dated debt and was “very doubtful that the ‘bonds are back’ theme is going to die.”

(Reporting by Dhara Ranasinghe and Nell Mackenzie in London, and Yoruk Bahceli in Amsterdam; Editing by Toby Chopra)